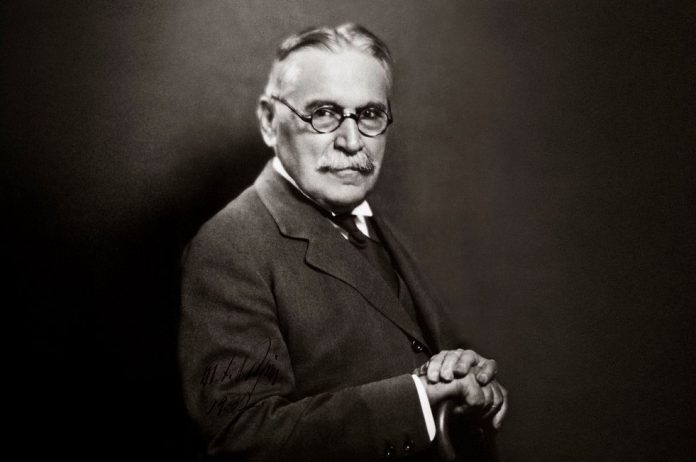

Famed Serbian-American scientist and innovator of Macedonian ancestry, Mihajlo Pupin, was US President Wilson’s special emissary for the Paris peace conference where he sought autonomy for Macedonia in 1919.

Journalist and writer Blazhe Minevski has explored Mihajlo Pupin’s involvement in the Macedonian question in his article published in Denesen Vesnik (09.09.2018). Minevski traces how the Macedonian question was treated in newspapers in the United States and by Macedonians living in the United States, Canada and Romania.

American publications extensively covered the conditions in Macedonia, as it can be seen from the countless articles taken from archives that made their way on the internet.

Minevski writes that the Americans were well-informed about the suffering of the Macedonian people in the years following the Ilinden uprising.

The “Eastern Question,” which is how the political situation in the Balkans was referred to over time, became the “Macedonian Question” because all of the nations had already won independence from Ottoman Turkey – with the help of respective Western powers or Russia.

Mihajlo Pupin, whose forefathers were born in the area of Ohrid before his family emigrated to Serbia, leveraged his reputation as a scientist to influence events in the Balkans.

Speaking at a meeting for emigres from Serbia and Montenegro, Pupin stated that the Balkan War, which had just begun in 16 October 1912, was not only a war against Turkey but also against the European diplomacy and especially against “the great powers who didn’t implement the decisions that were brought during the Congress of Berlin in 1878 concerning the Balkans.”

According to Minevski and his source, Dr Pavle Mitreski who researched the life of Pupin, the latter was referring in his speech to the Macedonian Question. The Congress of Berlin was supposed to bring autonomy to Macedonia and that would have created no need for the Ilinden Uprising or the Bucharest Treaty which partitioned Macedonia.

Pupin ended his speech with the words: “Let’s liberate our brothers in Macedonia, protect your women from the Turks, your daughters from the dangers of the harem, from slaughtering and pillage.”

In the meantime, the American media continued to inform about the conditions in Macedonia and the Macedonian emigration in the US and Canada was taking action by sending telegraphs and pleading with politicians for Macedonian autonomy.

US President Woodrow Wilson was concerned about the conditions in the Balkans and especially the Macedonian Question. In his 14-point peace program, Wilson states that the Treaty of Bucharest cannot resolve the problems in the Balkans because it was the product of the corrupt Balkan bourgeois.

US foreign policy sought a lasting solution in the creation of an autonomous Macedonian state which would later be able to form an alliance of independent Balkan states. This was opposed by Great Britain during the secret preliminary talks in London and Paris ahead of the conference.

Unfortunately, the proposals for Macedonian autonomy were not materialized into an act. One of the possible solutions was Macedonia to be given an autonomy as a protectorate of the United States.

Mihajlo Pupin provides a memorandum to US President Wilson in which he demanded a resolution of the ethnic and historic questions in Macedonia and Slovenia, but he was opposed by the Serbian representative and statesman, Nikola Pashikj, due to fears that the Bulgarians representatives are going to turn the Macedonian Question in their own favor during the conference.

In a separate Yugoslav delegation in Paris, according to the conclusions in the sixth point, Pashikj stated that America is inclined towards Macedonian autonomy and that if this idea emerges in the public, it will be very difficult to return the conditions to their previous state. Pashikj demanded that Pupin should prevent Wilson from seeking Macedonian autonomy.

Pupin’s concern with Macedonia will face obstruction from Nikola Pashikj, who became embedded in the politics of Serbia and Yugoslavia, for espousing the American ideal of “agitating for moderation from the great powers and demanding justice in respect to the small nations.”

Pupin sought various ways to help Macedonia. In addition to landing his reputation as a scientist, innovator and university professor Pupin created an educational fund and a poverty fund for poor children in Macedonia and donated from his own money for various causes.

Thanks to Pupin’s money, the Saint Clement church in Ohrid received the biggest church bell in the Balkans in 1923, weighing 2,300 kilograms. Amidst his friends, Pupin had called it “the bell for the liberation of Macedonia.”

According to his biographers, both of Pupin’s ancestors were from Moskopole, located in today’s Albania, which was once an important city inhabited by a mix of Vlachs and Macedonians.

Following the city’s destruction, Pupin’s parents relocated to an area near Lake Ohrid. According to Dr. Jovan Trifunovski, the Pupins lived in the village Nicha, not far from the Saint Naum monastery.

Two of their sons moved to Vevchani and the other two migrated to Serbia – Stojan settled in Banat and Konstantin – Mihajlo Pupin’s father, moved to another location. Mihajlo Pupin was born in the village Idvor in 1854.