Philip II of Macedon was born in 359 in Pella, the new capital city of Macedonia. Inheriting a weak Macedonian Kingdom, Phillip II used diplomacy, intrigue and sheer will to turn Macedonia into the first European empire.

His reforms in the army where revolutionary, creating the worlds first professional army that can battle in every season.

With his son Alexander III of Macedonia (the Great), Phillip conquered the Greek city states, Thracian and Illyrian tribes and fixed his eyes on the greatest empire in the world – the Persian Empire.

But how did King Phillip II get to this point?

Macedonia at the time of Phillip’s youth

Considering the condition of the land under the rule of his father, Amyntas III, Philip’s childhood and youth were primarily marked by his captive residence in enemy territory and by sibling rivalry.

We know that Philip’s mother was Amyntas’ second wife and that there were three children from his first marriage who were set to assume the throne.

In Macedonia and in other monarchic domains of the ancient world, like Persia, the offspring and kin of established monarchs engaged in cunning and court intrigue which often turned brutal, in their pursuit of the royal throne.

Philip’s father, Amyntas III, had a difficulty keeping his kingdom together due to incursions by Illyrians from the west and Dardanians from the north-west. These had led to devastating political and social consequences that required heavy diplomatic concessions on the part of the king.

One such concession was made to Bardylis, a military leader of an army of various Illyrian groups. According to the ancient historian Diodorus, Amyntas III had to give up Philip as a hostage at a very young age. This would have spared Amyntas III from incursions as long as he paid tribute to his nemesis in whatever form it was agreed upon.

The young prince remained under the Illyrians for ten years, from the ages of 3 until 13 according to ancient historian Justin. During the latter few years of Philip’s captivity, the Macedonian court became unstable, resulting in the regicide of Alexander II and the subsequent rise of Perdiccas III.

The Macedonians had resorted to buying their peace by means of sending Philip II as a hostage to Thebes, between 368 and 365. During this time he was in the company of powerful military men and learned about tactics and warfare. It was the knowledge he later implemented to reform the Macedonian army.

Return to Macedonia

Philip returned to Macedonia at the age of 18 and witnessed first-hand the troubling times under the political dominance of his old guardian Bardylis. The killing of his brother Alexander II by a rival and the subsequent slaying of his other brother Pediccas III by the Illyrians, fast-tracked the young Amyntas IV to the throne, which Philip dutifully seized.

From that moment, the 20-something was able to deploy all of the military knowledge he had gathered from the ascending Illyrians and from the then-waning military democracy of Thebes by giving a new sense of leadership to the Macedonian soldier class which had by then become desperate.

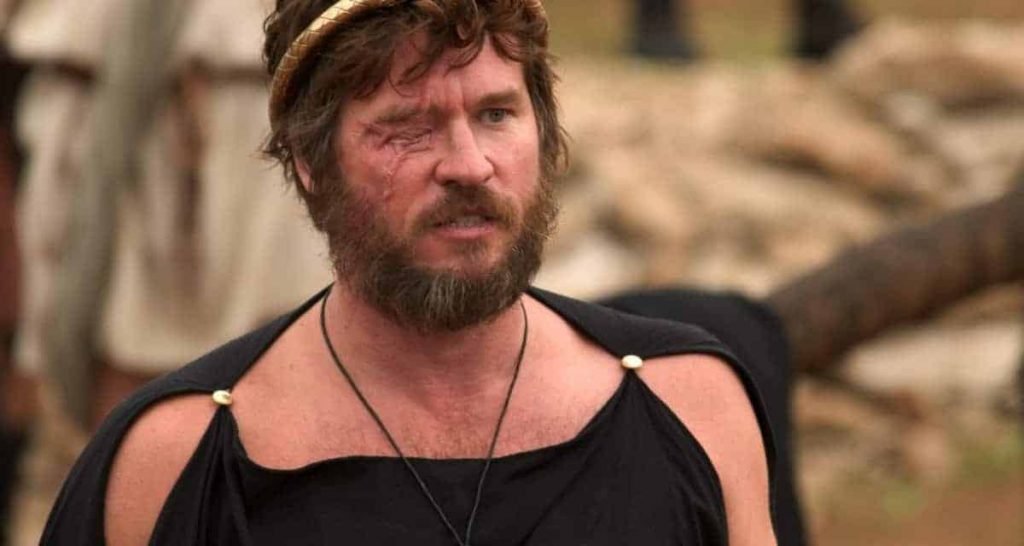

The young king, who then became known as Philip II, was known to the Greeks for his lewd lifestyle for which he was scorned and demonized by his Greek enemies.

Philip was able to command control of the Macedonian economy. He had allocated more agricultural land to the poor and expanded the grazing grounds of those who owned cattle and horses.

Philip’s predecessors were only able to mint coins in bronze and rarely in silver, however, he established firm control over the silver mines in Macedonia and began circulating his own coinage. His greatest resource, however, was timber.

Macedonia was a heavily wooded land, especially the Upper Macedonian highlands which coincide with the present-day Republic of Macedonia. Philip used this to his advantage to bribe notable figures in the Hellenic city-states. Demosthenes (19.265) accuses someone by the name of Laesthenes of having roofed his house with timber from Macedonia. He calls it “madness” and a “misfortune” to receive bribes from the Macedonian.

Philip’s shrew disbursement with finance and natural resources has led to the reversal of fortunes. As we can see from Demosthenes’ distress, Philip was able to buy himself access to first-hand knowledge of the military and political affairs beyond the control of his kingdom.

If we are looking for a psychological profile of Philip, we are looking at someone who was weathered by experience. While in captivity, he had to learn how to fend for himself from a very young age. Living in enemy territory, one can only imagine how he was regarded on a daily basis – he probably did dirty work, like shovelling and heavy lifting and heard no nice words from his supervisors.

A royal court like no other

His behavior at the Macedonian court was the complete antithesis of the upright and groomed democratic and military actors of the Hellenic city-states. Having wine-fueled laughs, catching a wondrous sight and being in the company of lewd women was perhaps Philip’s way of compensating more than a decade spent in servitude and compliance in Thebes and Illyria.

Philip organized large banquets where guests engaged in bouts of heavy drinking. Unlike the Greeks, the Macedonians didn’t mix their wine with water and succumbed to its powers in night-long benders, often resulting in fistfights and even murder. On one occasion, while heavily inebriated, he made a public scene exchanging insults with young Alexander, but couldn’t hold himself from charging at him. Fortunately for the son, the father stumbled and fell to the ground, prompting the young prince to finish off the exchange with a final stab at his drunken persona.

The historian Theopompus, who was a contemporary of Philip II, wrote that he was brutal, conniving and enjoyed splurging money. This latter trait was part of his go-to diplomatic tool-kit in buying loyalty from local warlords by marrying their daughters personally or off to his companions, which required dowry and gifts that were coveted by the patriarchs.

That Philip was a spendthrift can be seen from the litany of his whims and antics. Once, during a military drill in Macedonia, he was approached by a group of soldiers seeking their back pay, but Philip rebuffed an encounter by walking through them, making a rude comment and diving into a pond. It would have been certain that Philip will eventually pay their salary, but it sounds like at the moment, that money had been in the works as a part of one of his schemes.

Although Demosthenes, the Athenian orator who rallied Greek patriotic fervor against Philip II and regarded him as a barbarian from a land unworthy of procuring a slave, he also thought he was “the cleverest man under the sun,” according to Diodorus. Philip II secured a military victory in repelling the Illyrians and keeping the Thracians at bay. He secured a faithful alliance with the Agrianians – a warlike Paeonian/Macedonian tribe.

Legacy

Alexander the Great had made the famous speech in Mesopotamia which was indicative of Philip II’s role in starting the Macedonian empire.

Alexander prevented an all-out mutiny among his soldiers by reminding them it was his father who enabled the Macedonians to replace their animal skins with finer garments and secured their villages from the plunder of the Illyrians and Thracians and dutifully conquering those lands.

After taking control of his most immediate neighborhood, Philip turned south and defeated Thessaly, Athens, Thebes and Phocis. Alexander finished extolling his father’s achievements for Macedonia by saying “he didn’t confer more glory on himself than on the commonwealth of the Macedonians.”

Although Philip appears to have been a snappy hothead, quick to pull the dagger on a friend, this was only one side of his personality and to an extent, perhaps an image that he wanted to project and did so whenever it was deemed necessary.

We should recount that Philip II had seven marriages in total, demonstrating the extent of his diplomatic skills – that he was more eager to secure his rule by political means than by outright warfare. The very fact that he was able to set his foot in the door and walk away with the hand of this or that princess is telling of his ability to appear convincing when making grand promises.

Philip II was able to maintain relations with multiple adversarial states and switched in and out of alliances, which was due to shifts in power relations across the Balkans. That Philip II was not refined gentlemen is more than clear, and although he was missing an eye and walked with a limp due to a maiming injury, neither was he a brute.

The bringing of Aristotle to the Macedonian court to tutor his son Alexander shows his view of the world also included the importance of learning and science.

Assassination

Philip II died at the hands of one of his bodyguards, Pausanius, in Aegae in 336 BC. The reason for the assassination hasn’t been settled either by ancient or modern historians, as there are few possible explanations – one being his marriage to a Macedonian woman, daughter of a chieftain, which may have endangered Alexander’s eventual claim to the throne with his being of partial Macedonian descent.

Some scholars argue Philip’s assassination was Olympia’s doing and that Alexander was in on it. When Pausanias, the person committing the act tried to escape, he tripped and was immediately put to death by Alexander’s companions instead of being held alive and questioned.

Perhaps it was Alexander after-all and his ambition to rule instead of being in the shadow of a father whose erratic whims demonstrated instability instead of firm control over the multitude of political and military affairs.