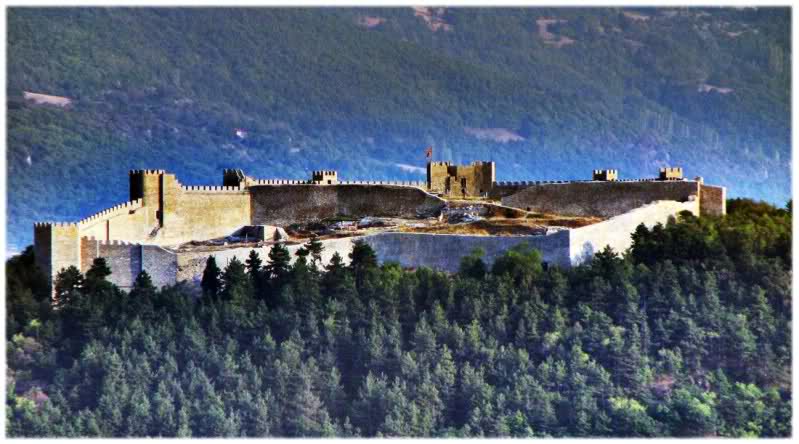

The fortress has a towering presence above Ohrid, and a mysterious past that has deep roots starting from the ancient Macedonian kingdom and continuing as the seat of Tsar Samuel’s Macedonian based medieval empire.

Popularly known as Samuel’s Fortress, recent archaeological discoveries have shown it was constructed into a grand fortress by King Phillip II of Macedonia, Alexander the Great’s father.

Further findings in Ohrid and the nearby village of Trebenishta have revealed magnificent golden masks and the Macedonian sun – consistent with findings across the border in what is now Greece and the rest of the Macedonian kingdom falling within today’s Republic of Macedonia.

Life-Changing Discovery

Simeon Karashov, an archaeology student at the time worked on the excavations of the fortress as part of Pasko Kuzman’s team.

Karashov talked to us about discovering an ancient Macedonian wine cup, featuring the national symbols of Macedonians – the Macedonian or Kutlesh sun.

“I was lucky enough to uncover one beautifully preserved black Megara wine cup. The Macedonian sun symbol, known as the Star of Kutleš, was engraved in relief form on the bottom. This cup is extremely interesting because of its very unusual shape. It looks like half a globe and it doesn’t have a typical stem with a foot,” says Simeon Karashov.

Ancient Macedonians were legendary drinkers and were known for their all-night binge drinking sessions – particularly after a battle.

The unusual form of the discovered wine cups confirms that in order to participate in a Macedonian drinking session, the social norm was the consume the wine in one go, bottoms up, and slam the cup on the table upside down once consumed.

“Imagine the sound it made being banged back on the table during a feast after a battle being won! Right here, in my home town, in my Macedonia! These people looking at lake Ohrid and the mountains behind the same way I do…”

One of the distinguishing characteristics that the ancient Hellenes saw in the Macedonians is that they drank their wine straight, that is, unlike the Hellenes who mixed theirs with water.

How Simeon Karashov came to discover the cup is fascinating. His experience lets us assume the same position as an ancient Macedonian noble in the past, who knows – maybe even Philip II of Macedon himself, in observing the cup as it is turned upside down – showing the ethnic/royal symbol of the Macedonians.

The cup was almost destroyed during the excavation reveals Karashov,

“A colleague of mine almost crushed it (the cup) with his shovel! With the edge of my eye, I saw the Macedonian sun peeking from the dirt, shining on the black ceramic so I yelled stop in a panic!!! Luckily we managed to pull it out in good shape. It felt as if I had just saved the world. When I held it in my hand for the first time, time stopped.”

Simeon Karashov attributes ancient artefacts as time capsules that enable people to feel connected to different periods that took place on the same land.

“I guess I could say holding the cup felt like I was holding a piece of myself. A piece of who I was before I became who I am today.

That’s what Macedonia is to me! An endless story laid out layer by layer from ancient times until today.

So much history in this land, it never ceases to amaze me. So simple and small yet so great!

The truth is, as a country we’ve fought endless fights because of this, but it is our destiny and obligation to preserve, protect, research and tell these stories to our children and to the rest of the world until the end of time.”

Origins of the Fortress in Ohrid

The earliest written evidence comes from the Hellenic historian Polybius (200 – 118 BC) who wrote the world-famous collection called The Histories.

He wrote that King Philip II of Macedon’s first military project in the city of Lychnidos (historic name of Ohrid) was to fortify it, but other discoveries reveal that there had been a fortification in Ohrid.

The archaeological work done in the area of Ohrid’s Varosh (old town) which includes the fortress and a location known as Gorna Porta (Upper Gate), turned up artefacts from the time of Alexander the Philhellene (lover of Greek culture) who lived in the 5th century BC.

It is conclusive that there had been some defensive and municipal structures in the area, as well as a fortification, however, Polybius’ account suggests that Philip II broadened the walls, made them taller and even expanded them along the eastern and northern slopes of the hill.

In the 2002 excavation, in which Karashov took part, the archaeologists discovered objects made of amber. Since the material originates from the area of the Baltic sea, we can conclude that there was a trade route from Macedonia to that distant part of Europe.

The hill around the fortress gives the area a remarkable view of the lake and had been used as a strategic outpost because it provided the inhabitants and their defenders with an expansive view of the Ohrid lake basin.

With the broad Galichica mountain to the east and the vast fields fit for agriculture all around, Ohrid could rely on significant quantities of food, clean water, timber, and other resources.

In fact, Philip II used the rich supplies of timber from Upper Macedonia, to which Ohrid belonged, to advance his political agenda in dealing with the Hellenic city-states.

It was only natural that Philip II ordered for a towering fortification to be developed on that location. This has made Lychnidos difficult to conquer, thus making the city a crucial deterrent against Illyrian advances and securing ancient Macedonia’s western border.

It is absolutely important to note that Lychnidos has been populated from time immemorial.

After all, Ohrid is the oldest and most remarkable lake in Europe, so it is no wonder that the area has been a major outpost of civilization.